by

Willard Van De Bogart

Language Center

Nakhon Sawan Rajabhat University

August 27, 2006

Abstract:

The methods developed for teaching conversational English are as varied as the English language itself. This paper outlines an approach based on pronunciation, vocabulary building and a situation specific role play model. The technique developed is based on a learning model that is repetitive in nature, with each lesson having the same structure for presenting the conversational English exercise. A systematic functional approach in presenting English conversation is used with each lesson being situation-language specific. A translation of the English vocabulary into Thai was also incorporated into each lesson plan. This provided the new learner with a quick reference by which to familiarize him/herself with each specific situation of the spoken English. The situation specific role-play model is so structured that it could meet a wide range of learner's needs and levels; be they professional, primary, secondary or college level students. Each specific situation was acted out in the class room, thus developing an acting role play model whereby students would actually be placed in a physical setting where they had to use the language for each specific situation.

Introduction:

The most universal need expressed by Thai students wanting to speak English is to be able to learn conversational English. Usually, this desire to learn conversational English is further clarified by Thai students requesting that they do not want to learn grammar, but only how to have a conversation using English. Although this may be the desire of the Thai student the truth is that some understanding of grammar is essential when learning how to have a conversation. I will discuss the use of grammar in this paper after I have reviewed the different role-play formats.

Nowadays, as Thailand is beginning to play a more prominent role internationally, learners of languages are realizing the benefits open to those who can speak foreign languages, in particular English and a demand for English proficiency in many institutions is desirable. This demand is not only for basic conversational English, but also for learning English to pass TOEFL examinations, for entrance into English speaking universities, making presentations at symposiums or professional organizations and greeting tourists who are increasingly choosing SE Asia as a preferred destination for vacations.

In writing this paper, I draw upon a plethora of experiences teaching English in Thailand to Thai students, both graduate and undergraduate, primary and secondary school level ranging from pathom 1-6 and mattayom 1-6, as well as government officials and employees. I have also taught English for Specific Purposes (ESP) courses for lawyers, doctors and nurses, accountants and many other professional disciplines. The ability to communicate in English is a necessary prerequisite in conducting business on an international level and in diplomatic exchanges. At this juncture, the present writer would like to point out that the majority of Thai students and professionals under his tutelage have not, as yet, had the opportunity or indeed been put in any situation which warranted the need to speak English. However, learning institutions, government agencies, and businesses are being required to raise the level of English proficiency for their students, employees, and staff in order to meet the ever increasing demand for English proficiency to operate effectively and productively as globalization now encompasses Thailand.

Consequently, many of the directors, presidents of educational institutions and administrative heads of companies are now responsible for making English more accessible to their subordinates, but are finding themselves at a disadvantage, by not having a basic command of conversational English themselves.

As a result of the findings from my own teaching practices in Thailand and being qualified in the Teaching of English as a Second Language (TESOL) I drew on my experiences both practical and theoretical, and set about attempting to redress the problem of teaching conversational English to Thai students.

The course produced, was oriented to specific situations whereby Thai students had to use English language to fulfill many basic conversation skills, such as how to ask for directions, buying something at a store or functioning within an office environment. I call this approach to learning basic conversational English the "situation specific role-play model". This approach also utilizes the native language experiences of Thai students, coupled with very careful monitoring of the spoken English in each of the lessons in order to give the Thai students confidence when using conversational English expressions in specific situations.

Harmer (1998), asks," why encourage students to do speaking tasks when learning English (p.87)? Harmer answers this question by stating that, "good speaking activities can and should be highly motivatingÉgive sympathetic and useful feedbackÉand use role playing as a task by which to enjoy learning English"(p.88).

The use of role-play in teaching English is by no means a new concept and the technique can be found in many textbooks designed to teach English as a second language.

Therefore, before outlining his own method in teaching conversational English the present writer would like to review, in detail, several published textbooks related to the teaching of English using role-play. First, let's look at the definitions for the two key components of this paper i.e. role-play and conversation.

What is Role-Play?

Harmer (1998), offers this definition,"Role-play activities are those where students are asked to imagine that they are in different situations and act accordingly"(p.92).

From my own teaching experience, I see role play as a vehicle by which students can more easily learn the fundamentals of English conversation in a specific situation, requiring the use of key words which act as signifiers for that particular situation. Stocker, Stocker (2006), state, "A Role-playing game (RPG) is a type of game in which players assume the roles of characters and collaboratively create stories"(p.1).

Applying role-play games to learning basic conversational English requires that the set and the setting, which is organized by the teacher, fosters as true to life a situation as possible where conversational English will be used. In this framework of a set and setting, the students act out their character roles so they can experience how conversational English is used in a specific situation.

What is a Conversation?

Chandra (1997) states that "a conversation is the informal exchange of ideas by spoken words. When we converse we engage ourselves in conversation about various subjects"(p.vii). This present writer would add to the basic definition of conversation by saying, a conversation is talking which takes place between two people.

Current research:

Prapphal (1998), found from her research that the English proficiency of Thai students who obtained their bachelors degree and who were tested using the (CU-TEP) Chulalongkorn University Test of English Proficiency, scored lower than that of students from other Asean countries. Prapphal emphasized that language teachers have to find new ways to help these students achieve their goals. Prapphal's number one goal was to ensure that Thai students could communicate English in social settings. What Prapphal is suggesting, is that the students become equipped with the skills that both academics and business sectors require. She further suggests a need to increase the student's motivation to learn English language in class, and even acquire the language outside the class. This could be achieved, according to Prapphal, by teachers changing their roles in the classroom, and introducing modern technologies into their language teaching practices. Both of these suggestions are noteworthy. But what were the roles, which needed to be changed in the classroom, so that facilitating an increase in English proficiency could be increased, especially, at the basic communication level? In this paper, I am going to address what roles need to be changed in the classroom by introducing an alternative method in using role-play to teach conversational English. I have already addressed the implementation of modern technology in the classroom Van De Bogart (2004). In this paper, the present writer would like to posit an approach which may develop the skills of the Thai students to communicate using English in social settings.

Cedar (2006), has recently published a paper on basic responses between Thai and American students. Cedar has uncovered some startling findings on the effects of socio- cultural norms and how they effect learning, especially, when a native English speaker is trying to teach Thai students. Cedar recommended teaching activities, which included role-play because role-play is an effective way to give students the experience of speaking English in social settings.

From the two researched materials we have examined, it may be suggested that teachers may need to develop their roles in the classroom, taking into consideration the socio-cultural differences between Thais and native English speakers.

Role Play Models:

The focus of this paper is to present an alternative approach to using role-play in the classroom for ESL students. From the above mentioned research conducted by two Thai researchers, it was found that there had to be a re-thinking as how to approach teaching English to Thai students, and I would add, conversational English. Both Prapphal and Cedar suggested role-play as a recommended teaching activity to improve Thai students use of English. There are far too many role-play models to mention in this paper, so the present writer will examine only several most commonly used. I have selected role-play models that have an easy pattern of role-play recognition for the Thai students to learn from.

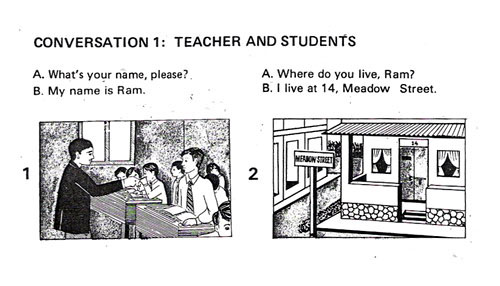

The first role-play model is found in Richards (1982). Richards includes fifty-five different role-play situations whereby the student has to use conversational English. Each lesson has a set of pictures, which show a specific situation in which the conversation is going to take place. The format of the lesson is so designed that on top of each picture there is a basic Q&A; conversation indicated by the AB format as shown in (figure 1.)

Picture #1, directly underneath the conversation, shows a person standing in front of another person who is behind a desk suggesting that A is asking B his name. This AB format is followed throughout the entire book. After each lesson, Richards suggests that the AB conversation format script is removed and the student is then asked to re-enact the conversation using the conversation they learned with the AB conversation format. At times the sentences in the AB role-play model, offered by Richards, are much too long for the Thai students to speak comfortably. The use of the picture, however, is the strong point in the Richards role-play model, but it doesn't encourage enough useful inter-activity for the students. So, although the model is useful, it falls short of placing the student in a real life situation to learn the appropriate or beginning conversation in each situation.

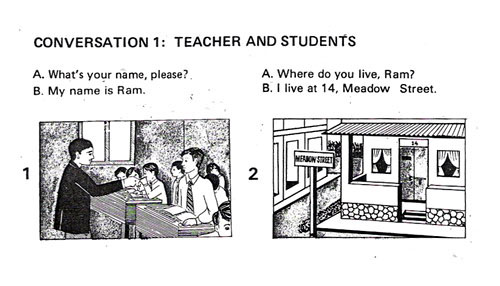

The second book role-play model is found in a book by Richards and Long (1984). This is a much more comprehensive book. The roll-play model in this book uses 14 different situations with eighty percent of the whole book placing emphasis on listening and speaking. The objective of these role-play models is based on a communicative approach to English, whereby students practice conversations in each situation. The role-play model begins with the use of a picture of a specific situation (figure 2) and followed by two more sections one of which is called, "Ways to say it" using the AB format, and a pair up and practice section, which also uses the AB format.

Each chapter follows the same organizational approach to the material, giving a secure foundation from which to learn. Also included is a reading for understanding section in each unit, followed by an understanding section, which includes questions and vocabulary.

For a beginner to English conversation, the actual text used in the conversations may be too difficult to learn immediately. The sections mentioned in the Richards and Long text are well planned, however, the implementation of each section will require more focus by bringing each section to the students attention in a step by step fashion. Richards and Long, have included all the basic role-play parts, and with the proper attention and guidance by the teacher, this can be a very useful beginners book for conversational English.

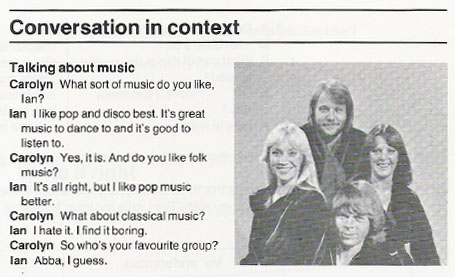

The third role-play model is found on a web site developed by Pereira (2004). Pereira's technique uses unambiguous visual information using his own "pic-word" format which allows the elements of a particular situation to be more coherent and easily understood by the students. (figure 3.)

Pereira and his colleague Samuel Schenker developed the "Stimu-Con Usage Game" using their "pic-word" format in Japan, emphasizing conversation as it is spoken in America, finally, resulting in the American Conversational Usage Games.

Pereira was aware of the dissatisfaction of expressions, which existed in the two cultures of Japan and America and therefore, developed a multi-usage game whereby many conversational expressions were suggested for each situation. What is unique about the Pereira and Schenker "Stimu-Con Usage Game" is that it allows the students to use many expressions, which mean the same thing. The images are drawn in a cartoon form with multiple responses given for a particular situation. There is no ambiguity in what the students must do using the pic-word game. I will expand on the "Stimu-Con Usage Game" after reviewing one more role-play format.

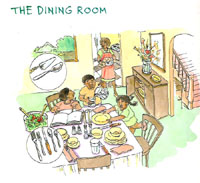

The last role-play model is from Carver and Fotinos (1998). The authors have made every attempt to make a very comprehensive role-play book incorporating the students experiences and interests. The book uses a variety of cross cultural experiences and interests and a very illustrative graphic where the specific conversation takes place.(figure 4.)

There are 10 units, which make up the book, and each unit is further divided into10 specific situations. Every aspect in teaching conversational English is provided for the ESL teacher wanting a comprehensive conversation book. I would emphasize the book is more teacher centered than student centered. At the end of each section of the main text there is a reference made to the appendix for an example of a conversation, which is correlated to each unit. These conversations are composed of sentences in the AB format, which are very lengthy and not easily understood by a Thai beginner student. A Thai student requires a basic foundation with which to build confidence in speaking a second language and especially with English. Carver and Fontino have created a wealth of material with which the teacher can develop lessons but it may not be appropriate for a learner. However, all the ingredients are encapsulated in the book, and there are a multitude of ideas with which the teacher can develop his/her role-play version.

Review of the four texts:

1. Conversation in Action

2. Breakthrough: A Course in English Communication Practice

3. Pragmatics and American Conversational Usage

4. A Conversation Book: English in Everyday Life

Each of these texts has been developed, in a practical way, so as to bring the student into a role-play format by which to practice situation specific conversational English utilizing the AB format. It is at this point in the paper that I want to single out a few details prevalent in each of these approaches to teaching conversational English.

Although the AB format appears extremely easy to use and understand, the fact is that the role-play model using the AB format does present some difficulties. The beginner student does not have a full comprehension of why he/she is speaking the words which come after A and B on the role-play conversation cards. The role-play exchange in pairing individual students, or dividing a class into groups still does not convey when to use the expressions following A and B in the AB format.

Carver and Fotinos (1998) use one picture, which shows the complete environment where the conversation is going to take place. Pereira (2004) uses the multi option list of expressions with the "pic-word" scenes for A and B. Richards (1982) uses a series of pictures with two sentences above each picture, and lastly Richards and Long (1984) have many choices leading to a conversation. Each format has its positive points, which are summarized here briefly. Richards (1982): Single picture with one question and one response using the AB format.

Richards and Long (1984): Single picture with a complete conversation next to the picture using personal names rather than the AB format. Pereira (2004): Cartoon showing two images with one question and a multiple of responses. Carver and Fotinos (1998): Picture showing a specific situation where many classroom activities are suggested preceded by a vocabulary list related to the activities.

An Alternative Role-Play Approach:

I would like to introduce another role-play model using the AB format in exposing the Thai student to basic conversational English. This approach uses "situation specific role-play conversation cards". Traditionally, role-play cards have been used to encourage students to ask questions. The questions are placed on small cards and used with a paired partner. Stocker and Stocker (2006) have developed an example of role-play conversation card questions.

Stocker and Stocker have a web site called, "Karin's ESL Partyland", which now includes a new section titled, "Ideas for Using Conversation Questions". For the beginner Thai student, however, who is using English for the first time, these questions are much too lengthy and the questions are beyond the conversation skills of a beginner. Below is an example of KarinÕs Conversation cards. (figure 5.)

Karin's ESL PartyLand/ ©1999 by Karin M. Cintron

Conversation Questions: Shopping

| What was the last thing you bought for yourself? How often do you go shopping? |

Where did you buy it? How much time do you spend each time you go? |

| Why did you buy it? What was the last thing you bought for someone else? |

Do you enjoy shopping? Where did you buy it? Why did you buy it? |

These questions are then cut into small cards and used by the students. I mention these conversation cards because it is suggested that the questions are cut into individual cards, which the student can then carry and read in the role-play situation. These conversation cards are very good for a student to use provided they can understand the questions and likewise be able to give an answer. Although useful, this type of conversation card does not model a real life conversation.

Part of the challenge in the classroom in doing role-play, is to stage the situation in which a specific conversation is going to be used. This type of role-play borders on drama or role-play acting. Developing a specific conversation, I believe, is more useful in learning about a conversation than merely asking a partner questions.

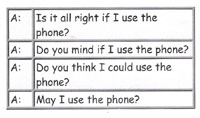

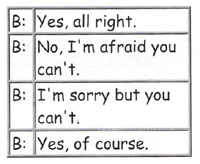

Cintron (2006) has written an excellent English language teaching article on role-play. He states that, "one of the most difficult and frustrating things is making the transition from the classroom to the real world"(p.1.). Recognizing this difficult transition from the classroom to the real world was the motivating factor in developing a set of "situation specific role-play conversation cards". The AB format was retained in the design of the cards, but rather than having only one role-play card, two separate cards were designed and linked together. One card contained the (A) format (question) and the other card the (B) format (response). The cards sets were coded with each other so they couldn't get mixed up, and included a photograph of the specific situation. One card was coded as A1 and the matching card was identified as B1. The coding helps to identify the cards so the students could easily exchange several card sets in the classroom without getting them mixed up. Each "A" card had four questions, and each "B" card had four responses. Having a set of these conversation role-play cards was only the first step in using the cards. An example of a conversation card set demonstrating how to make a phone call is shown below. (figures 6a, 6b, 6c)

-

-

Step One: Using the "situation specific conversation role-play cards".

The students are asked to read the sentences on the cards out loud, so they can repeat the sentences for their partner, and in turn, their partner can respond back with their sentences.

Step Two: Becoming familiar with English with the role-play cards.

The students are asked to make sure they understand the meaning of each word in the sentences. By knowing the meaning of each word in the sentences, the students in turn can understand the words that make up the conversation. The lesson includes a vocabulary list introduced at the beginning of each lesson showing both the vocabulary in English and a translation of the vocabulary into Thai. This technique is used to insure that the subject they are going to have an English conversation about is, at least, identified in their own language. Below is an example of translated words expressing like or fondness.

Like words:

Like

Love

Lovely

Fond

Interested

Terrific

Yes

Very

Fairly

Me too

Knowing the meaning of the translated English words does not help in understanding how the English words are used in the context of the conversation, but they do give the student some reference when reading the English sentence. After repeating the AB sequence from the conversation cards the students begin to expect a certain response from their partner. The students take ownership of their conversation cards because without the cards the students could not dramatize the conversation.

Step Three: Dramatize the specific situation using the conversation cards.

In was in this step, the students were then asked to participate in a very simplistic mock setting in the classroom using their conversation cards. This technique is both drama and role-play at the same time. No longer was the student in a sitting position reading the English sentences on the role-play cards to their partner, but now had to actually get up and walk to the mock setting, which was placed in the classroom by the teacher.

Example of a Mock Setting:

If there is a white board on wheels in the classroom ask one of the students to stand on one side of the white board. Tell the students the white board represents a department store (BIG C) and one student is inside BIG C waiting to meet their friend. Ask the student who is going to Big C to meet their friend by walking around the white board and meeting the other student (their friend). Then ask the student who is waiting for their friend in Big C to greet the student coming into Big C. It's extremely simple and sets up a real context where somebody is meeting someone. The students then read their conversation cards, and the experience, for the first time, the English language in a specific situation rather than reading about a conversation in a textbook. When the students first act out their role-play, it will cause a lot of laughter because they realize how awkward it is to greet someone by reading off a hand held card. But the lesson is grounded in a realistic situation, so the student learns which sequence of words is used in each specific situation, and after several attempts can memorize which to use without the aid of the card. Recalling Pereira's multi-level approach with the "Stimu-con Usage Game" its possible to create the conversation cards including many different conversation exchanges which mean the same thing. I chose four different basic conversations for my "situation specific role-play model". What I discovered is that the students will remember the easiest conversation for each specific situation. There is nothing wrong with that. By remembering one conversation sequence is the beginning of building a basic foundation where the student feels confident in repeating a response for each specific situation. This is an accomplishment for the Thai student and they will remember it as they learn more conversations in additional lessons.

Step Four: Dramatization without role-play cards.

After the students finished their dramatization using the conversation role-play cards they were then asked to do the same role-play without the use of the cards. It was at this point that spoken English without a prompt was first introduced to the student. Invariably, on the first solo conversation attempt only a few words would be remembered from the cards and a very broken English conversation would take place. This is where the teacher would then support the student by filling in the word gaps to the conversation and congratulating the student for their first attempt at having a conversation using English. Many times it would be necessary to prompt each student by reading aloud a word from one of the sentences on the conversation cards. Once the sequence is remembered, and spoken correctly, it is important to recognize this achievement by the student. It is important to build the students confidence by helping the student choose the appropriate words to complete the conversation in each situation.

It is essential in teaching conversational English that the words, which are used in each specific situation, are followed up immediately with approval to boost the student's confidence.

In a real world situation there are many unpredictable events that can take place in the context of a specific situation. By giving the students an opportunity to speak without using the conversational role-play cards, as well as speaking in a non-threatening environment, provides a safe atmosphere for active learning where the student is required to use English.

Kodotchigova (2001) has developed role-play steps for classroom implementation in Russia. Her advice is to let the students decide which situation they want to learn in an English conversation. Subsequently, a special class of students from Chinat, Thailand came to Nakhon Sawan Rajabhat University for the sole purpose of learning conversational English. Kodotchigova's suggestion was implemented and a questionnaire was given to the students to determine what aspects of conversational English they wanted to learn. The experience of the students from Chinat ranged from high school students (mattayom 6), to professionals who had not practiced English for twenty years, but needed to know how to have a conversation in English. The students produced a list of the specific situations in which they wanted to speak English. The topics the students wanted to gain conversation experience in were:

1. Telling someone what they want.

2. Daily life conversations i.e the telephone, in the office, etc.

3. Asking about prices.

5. Offering to help people.

6. Apologizing.

7. Showing likes and dislikes.

8. Giving a compliment.

9. Giving a greeting.

The class met once a week for four hours for twelve weeks. It was this class that the "situation specific role-play model" was first introduced. A special evaluation form was designed for the students after the course was completed. All the students gained more confidence in using conversational English in specific situations as a result of practicing with the "situation specific conversational role-play cards.

Conclusion:

From what has been discussed in this paper it may be suggested that teachers need to take into consideration many elements when designing a conversation English course, which would be in addition to the listening and speaking courses. Conversations are based on requests, which require very specific responses in English language. When you look at the topics selected by the Chinat students, itÕs clear what was important for them to learn.

There are many textbooks, which can be used in teaching conversational English. However, what I have discovered in teaching a basic approach to conversational English, is based more on encouraging the students to participate physically in the conversation with a dramatization of a specific situation where English is going to be used. A student can learn textbook lessons, but acting out the lesson in a mock situation using role-play, gives the student a better experience of speaking English in a specific situation. Acting out a specific situation with role-play is closer to the real world of conversational English, than just repeating phrases from a textbook or out of context where the actual English is going to be used.

How to get the students to remember their own specific conversation and feel confident when they are asking questions and offering their responses can be aided if the students have their own conversation cards. ItÕs a step by step process to achieve a conversation much unlike grammar, which requires a list of rules when using verbs, nouns, adjectives and a great deal more of unique parts of speech.

Grammar is implicit in the conversation. Grammar can be taught independently from conversational usage or partially emphasized when learning a specific conversation. The two facets of a conversation are being grammatically correct, and at the same time conveying the proper meaning. In a conversation the students want to be confident they are speaking English that's appropriate for a specific situation. Once the student can produce specific conversational phrases proficiently then the grammar can be taught with the conversation. The goal of all basic English conversation courses is to provide the student with the skills to speak in a real life situation, using the appropriate words to convey a request, and understand the response. I have found that using "situation specific role-play cards" enables the students to learn conversational English more rapidly than conventional approaches, and develops the students self confidence when using spoken English. This technique is simple, effective, and learner friendly, and above all, fun.

References:

1. Carver, T.K., Fotinos, S.D. (1998) A Conversation Book 1: English in Everyday Life. New York: Prentice Hall Regents

2. Cedar, P.(2006). Thai and American Responses to Compliments in English. The Linguistics Journal, 2, 9-10. Retrieved July 15, 2006, from http://www.linguistics-journal.com/June2006-pc.php

3. Chandra, R. (1977). Self Help to English Conversation. New Delhi: Goodwill Publishing House.

4. Cinton, K.M. (1999). Karin's ESL Partyland: Teaching Conversation. Retrieved July 15, 2006, from http://www.eslpartyland.com/teachers/nov/conv.htm

5. Harmer, J. (1998). How to Teach English. England: Addison Wesley Longman.

6. Kodotchigova, M. A. (2001). Role Play in Teaching Culture: Six Quick Steps for Classroom Implementation. Retrieved July 25, 2006, from http://iteslj.org/Techniques/kodotchigova-RolePlay.html

7. Pereira, J. (2004). EFL Japan: Pragmatics and American Conversational Usage. Retrieved July 20, 2006, from http://web.kyoto-inet.or.jp/people/sampachi/efl/pragma/pragma1.html

8. Prapphal, K. (1998). English Proficiency of Thai Learners and Directions of English Teaching and Learning in Thailand. Retrieved July 25, 2006, from http://pioneer.netserv.chula.ac.th/~pkanehan/doc/EnglProfLearnhailand.doc

9. Richards, J.C. (1982). Conversation in Action. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

10. Richards, J.C., Long, M. N. (1984). Breakthrough: A Course in English Communication Practice. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

11. Stocker, G., Stocker,D. (2000). English Language Teaching Articles: ESL Roleplay. Retrieved July 19, 2006, from http://www.eslbase.com/articles/roleplay.asp

12. Van De Bogart, W. (2006). Experiences Introducing an Internet-Based English Course. PASAA: A Journal of Language Teaching and Learning in Thailand, 38, 97-101.

13. Van De Bogart, W. (2004). How to Help Thai Students Develop Ideas and Express Opinions. Retrieved August 15, 2006, from http://www.earthportals.com/rajabhat.html

14. Van De Bogart, W. (2004). Internet Based Learning with ESL. Retrieved August 15, 2006, from http://www.earthportals.com/Portal_Messenger/thaitesol.html

15. Wikipedia, (2006). History of role-playing games. Retrieved July 17, 2006, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Role_playing_game